‘Hypotonic polyuria’ is when you produce large amounts of dilute urine and is a symptom of three possible endocrine conditions:

- AVP deficiency (AVP-D, previously known as central diabetes insipidus)

- AVP resistance (AVP-R, previously known as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus)

- Primary polydipsia (PP)

Finding out which condition is responsible for causing hypotonic polyuria and subsequently managing this condition can pose challenges for clinicians. There have been advances in diagnostic techniques in recent years and it is becoming more common that clinicians will use a technique called ‘copeptin measurement’ to investigate the root cause of hypotonic polyuria.

A recent research article, co-authored by Deborah Cooper (a Pituitary Foundation Trustee), Professor John Wass, and Professor Miles Levy (members of our Medical Committee) looks at three different patient cases where copeptin measurement was used to diagnose an endocrine condition. These cases highlight how copeptin measurement can be a better diagnostic tool than other techniques, such as the water deprivation test. In this blog post, we explore what copeptin is, how it can be used for diagnosis and why it may be preferred over other techniques, such as the water deprivation test.

What is copeptin and how can it be used to diagnose endocrine conditions like AVP-D?

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) is a protein made in the body using many smaller protein building blocks. Its normal function is to prevent the passing of excessive amounts of urine. If there are issues in the production or function of this protein, it can lead to AVP deficiency.

One of the protein building blocks used to make AVP is a small protein called copeptin. Copeptin is released in the body proportionately to AVP, meaning that the amount of copeptin in the blood mirrors the amount of AVP. As copeptin is easier to test for in blood, this makes it a good way to assess how much AVP the body is producing. If there is a low level of copeptin in the blood this would also mean there is also a low level of AVP. Therefore, measuring copeptin can be used to help diagnose AVP-D, AVP-R or primary polydipsia (PP).

Why can’t we measure AVP instead of copeptin?

It can be very difficult to accurately measure the amount of AVP in the blood, for different reasons:

- AVP in samples breaks down quickly, making it hard to measure accurately once the sample is taken. Copeptin is more stable than AVP, meaning it takes longer to break down and therefore is easier to measure accurately

- There are not many tests available to measure AVP and the ones available take a long time to give results

- A large amount of AVP in the blood is not detected by tests, which can give incorrect readings

Why might measuring copeptin be better than a water deprivation test?

Anyone who has experienced a water deprivation test will be aware of how uncomfortable they can be. The test usually involves stopping someone from drinking water, usually for up to 8 hours but sometimes for longer. This is to assess how concentrated their urine becomes.

As well as being very uncomfortable, a water deprivation test may also not have complete accuracy when being used to differentiate between whether someone has AVP-D or PP. Also, if a patient has PP then there may be very large amounts of water in their system from having drunk so much. This means it can take even longer for them to become dehydrated for this test, which can be very uncomfortable.

What type of diagnostic test is right for you?

Your GP or endocrinologist will choose the right diagnostic tests for you based on your symptoms and medical history. Your clinician will also assess your fluid intake and output over 24 hours, for a couple of days.

Copeptin tests are currently used by the NHS and it is possible that patients may be able to request a certain diagnostic test, although it will depend on other factors (as mentioned above) as to whether certain tests can be used or not.

Overall, using copeptin levels to diagnose vasopressin-related endocrine disorders can provide more accurate and timely diagnoses, which can help ensure that patients receive appropriate care and management of their symptoms. Historically, these conditions have proved difficult to diagnose so hopefully advancements in diagnostic processes will mean that endocrinologists will be better able to diagnose and manage these conditions.

You can read the full article here. You can also find out more about AVP-D and AVP-R, including diagnosis and treatment of these conditions.

References

- Approach to the patient with suspected hypotonic polyuria; JCEM; 2025;110(2);

- Copeptin and its role in the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis; Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019;91(1):22–32;

- The emerging role of copeptin; Clin Biochem Rev. 2021;42(1):17–25

To mark Rare Disease Day 2025, we’re showcasing stories from our community to raise awareness of rare diseases and the way they can impact people’s lives. In her story, Sophie shares how she struggled to receive an accurate diagnosis of Cushing's, despite continuously pushing to be listened to. She describes the inspiring ways that having a rare disease has changed her outlook on life.

Sophie's story

Let’s rewind to 2022. I had just turned 30 and was looking forward to the next decade of my life. It started off great with birthday celebrations, spa days, holidays, concerts, so many plans with friends and family and then things slowly started to change.

I started to notice that I was losing a lot of hair which was really unusual as I’ve had lovely thick, long hair my entire life and always taken care of it. I thought it must have just been something or nothing so I ignored it. A few months went by and I was still losing my hair and now my periods were becoming late every month, so I booked an appointment with my doctors. Over the next year, I started having blood tests and ultrasound scans but everything was coming back normal.

Fast forward to early 2024 I was still going to the doctors, they kept telling me there was nothing wrong with me. I knew I wasn’t ok, I could feel it, I knew something was wrong. By this time I hadn’t had a period in over 9 months and I had lost 2/3 of my hair. Not only that I had put on nearly 2 stone in weight even though I exercised twice a day and ate a balanced diet, my face was getting rounder and more inflamed, my skin was changing all over my body and I couldn’t sleep no matter how hard I tried.

I went back to the doctors one last time and the tests came back again that everything was ok and I probably just have PCOS even though I had been tested and the scan came back clear. I was told because the symptoms were similar that this is what it must be. So I was diagnosed with PCOS and sent on my way. I was about to give up as it was so draining to keep being told that there was nothing wrong, but I knew it wasn’t PCOS. Something just didn’t feel right, so I went private to have some tests done and what happened from there took me on a life changing journey.

A medical professional during a brief conversation made a passing comment about a rare disease. I hadn’t heard of it and didn’t think anything of it at the time, but that evening at home I googled it and this image came up on screen of a depiction of a person who had this disease. Well, it was like looking in a mirror. I looked just like that image, so I started to do more research and low and behold I had every single symptom listed. Everything just started to make sense. It was now March 2024 and by this point I was very unwell but still hadn’t got a diagnosis, not even close. I asked my private consultant to run some tests specific to this rare disease. I knew at this point I needed to be on the NHS waiting list for treatment so I emailed my local endocrine consultant advising I was having tests done privately and if he could take me on as a patient if the tests came back positive. To my surprise I received a letter in the post in response to my email that he would add me to his clinic if the results came back positive. Whilst I was waiting for my results to come back, I took a turn for the worse and ended up being admitted into hospital. During my hospital stay my test results came back from my private consultant and everything started to become clear. The NHS endocrine consultant was notified and further testing took place, and it was starting to look more likely that it was in fact this rare disease.

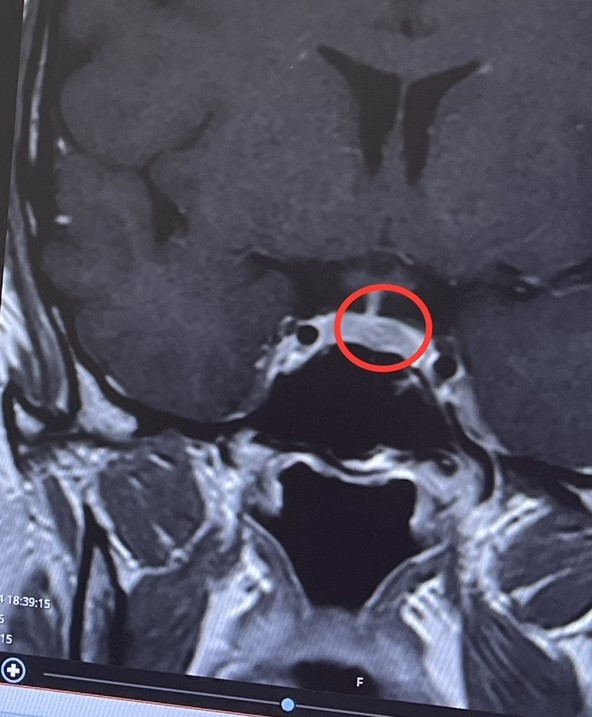

Over the next few weeks/months I had many specialised tests, blood tests, scans, MRIs etc. During this testing period I became so unwell, my symptoms were worsening by the day. I was on so much medication to just help me survive. I was in hospital at least once a week having various tests. By this point I had completely lost my identity; I couldn’t recognise myself. It was taking its toll on my emotional and physical health. After months of invasive tests and scans I was finally diagnosed with Cushing’s disease caused by a pituitary tumour. They had found a 9mm tumour in my pituitary gland that was secreting excessive amounts of cortisol which was causing unspeakable damage to my body. To get the official diagnosis was a relief after being told for nearly 2 years that there was nothing wrong with me. I finally felt validated but also terrified at the same time. My health was deteriorating very fast and surgery was the only option to remove the tumour.

My consultant fast-tracked the surgery and I was referred to the neurology team. Within a week I was in for my pre-op and my surgery date was given. D-day arrived: on the 8th November I underwent transsphenoidal brain surgery to remove the tumour in my pituitary gland. For better or worse, that day changed my life.

I am now 3 months post-op and trying to navigate my new normal. I’m steroid dependent as my body is no longer producing cortisol. I have adrenal insufficiency and due to damage to my pituitary gland during surgery I now have AVP deficiency. My life looks very different to how it used to. I’m not the same person I was before my diagnosis but one thing I am thankful for is that I’m here and I’m alive. The last 12 months have been traumatic, emotional, frustrating at times and exhausting but I wouldn’t have been able to get through it without my close friends and family and my consultant, his secretary and all the other NHS staff.

I don’t know what the future has in store for me but for now I will continue to recover and take the small wins everyday. Everything happens for a reason. I’m unsure as to why this happened to me, but I have a feeling its because I’m here to help others. In what capacity I don’t know but I’m looking forward to the journey.

Living with a rare disease

Living with a rare disease can be overwhelming and scary. Firstly, it can be difficult as people have never heard of it and it's unlikely you will come across people in your circle that have, let alone someone actually being diagnosed with it. The one thing I struggled with with having a rare disease was that no one around me could understand what I was going through; no one could relate. That was until I found a support group on Facebook and the resources available through The Pituitary Foundation.

Being diagnosed with a rare disease doesn’t mean your life is over, it actually enables you to re-evaluate your life and focus on what’s important. Sometimes you just let life pass you by as you’re busy with work, looking after kids, family or friends etc, and within all that you forget to live. Having been diagnosed has allowed me to take a step back, look at my life differently and now I’m ready to grab it with both hands and truly live my life with no regrets. Life is far too short so strap in and enjoy the ride.

Thank you Sophie for sharing your story! If you would like to share your story with the pituitary community, please email [email protected]. Views and experiences expressed in stories of those of the community member and do not necessarily reflect The Pituitary Foundation.