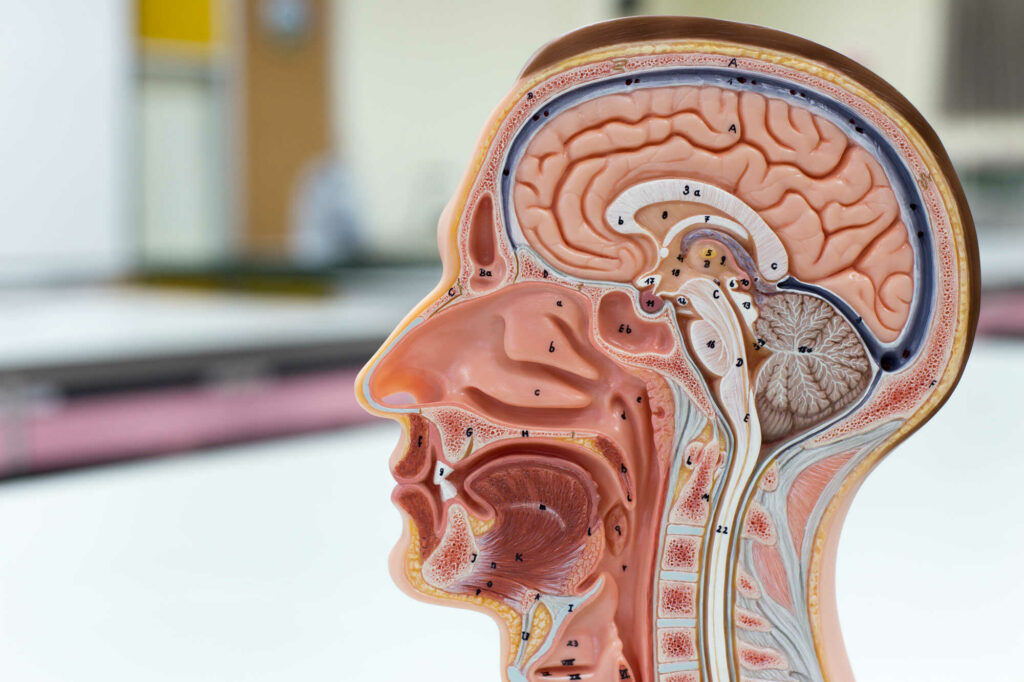

What does the pituitary gland do?

The pituitary gland secretes hormones from both the front part (anterior) and the back part (posterior) of the gland. Hormones are chemicals that carry messages from one cell to another through the bloodstream.

If the pituitary gland is not producing sufficient amounts of hormones this is called hypopituitarism.

If hormones are being over-produced, then this can cause problems depending on the hormone creating concern.

The Society for Endocrinology has more information about the pituitary gland, including educational resources on their site You and Your Hormones.

The hypothalamus

The hypothalamus, which controls the pituitary by sending messages, is situated immediately above the pituitary gland.

This serves as a communications centre for the pituitary gland, by sending messages or signals to the pituitary in the form of hormones. These travel via the bloodstream and nerves down the pituitary stalk. These signals control the production and release of further hormones from the pituitary gland signalling other glands and organs in the body.

The hypothalamus influences the functions of temperature regulation, food intake, thirst and water intake, sleep and wake patterns, emotional behaviour and memory.

What can go wrong with the pituitary gland?

The most common problem with the pituitary gland occurs when a benign tumour (used to describe a ‘growth’), also called an adenoma, develops. The term benign is used to describe a swelling which is not cancerous.

Most pituitary tumours occur in people with no family history of pituitary problems and the condition is not usually genetic. Only very occasionally are tumours inherited – for example, in a condition known as multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN1).

Pituitary tumours are not ‘brain tumours’. Some pituitary tumours can exist for years without causing symptoms and some will never produce symptoms.

By far the most common type of tumour is the ‘non-functioning’ tumour.

This tumour doesn’t produce any hormones itself. It can cause headaches and visual problems, or it can press on the pituitary gland, causing it to stop producing the required amount of the pituitary hormones. This effect can also occur following treatment given for a tumour, such as surgery or radiotherapy.

Alternatively, pituitary tumours may begin to generate too much of one or more hormones.

The more common pituitary conditions include acromegaly, Cushing’s, diabetes insipidus, hypogonadism, hypopituitarism and prolactinoma