I’m 47 years old and it has been 17 years since my first symptoms and I guess I have at least another 17 years of brokering a truce with my pituitary gland. Hence my 'middling' status.

I have ‘controlled Cushing’s disease’. I’ve had two semi-successful pituitary surgeries and six weeks of radiotherapy, which completed on Halloween 2022. The last three years have been quiet - no signs of the feared regrowth or of the predicted pituitary failure. We watch and we wait.

Across the board it’s a mixed bag of changes. I am producing healthy amounts of cortisol myself (no steroids - yay!) and I am only replacing thyroxine and vasopressin BUT I still have most of my symptoms. I’m oppressively fat, I’m frustratingly weak and my blood pressure is worryingly high. Thankfully the oedema in my ankles is better as long as I keep my feet up regularly.

Some small wins - I no longer bruise so readily, the purple stretch marks on my tummy have turned silver and my head hair is gradually thickening and growing again. My chin hair lingers sadly… The radiotherapy caused my toenails to be crumbly until quite recently, so I can now wear sandals with pride!

How do I fill my days?

In a nutshell, I’m currently fully retired. Not quite how I imagined spending my 40’s but here I find myself!

I used to be a primary school teacher and, between surgery one and surgery two, I tried a gentle return to school. I took on roles as an intervention tutor, a supply teacher and then a part-time PPA (planning, preparation and assessment) teacher. In all those roles, I could get away with sitting down quite a bit and there were no break duties etc but quite frankly I was barely managing and it wasn’t sustainable. During the weeks after surgery two in March 2022, I came to the realisation that teaching as I knew it was over for me.

As it happened a close family member died during my treatment and just when I’d run out of earning power, a block of money arrived in my life. Quite frankly, I would rather have kept my teaching job and said family member but it was not to be. As a result, I have a mid-life pension. It won’t last forever and I’m not rolling in it but it’s enough to fund my rehabilitation efforts and protect me from having to rush the process.

In terms of my week, I spend about 70% of my time engaged in what I call ‘body management’. Therapeutic things like sessions in the swimming pool to get my joints moving, yoga and meditation to sooth my bruised brain, lymphatic massages for my oedema and talk therapy to help me make sense of everything that has happened.

The remainder is spent doing musical activities. Before I was a teacher I was a french horn player - orchestra tours, solo recitals, auditions etc etc. This revival of a past self has somewhat crept up on me. It started 2 years ago when my yoga teacher suggested we include meditation to music in our sessions. She would curate a playlist of her choosing and I would sit in my wheelchair, close my eyes and engage in deep listening. It felt like I was visiting a far-off place of sacred importance without having to move a muscle (phew!).

Looking ahead…

Since those sessions, my musical environment has expanded somewhat. I attend concerts as much as I can and I’ve joined a choir. I’m having one to one singing lessons, I’m about to start song-writing lessons, and last Christmas I visited my father abroad to both say hello and to extract my much-neglected french horn from his loft. I’m not quite ready to get it out of its case yet but suffice to say that I’ve got the number of a local brass instrument repairer and when the time is right my newly serviced Yamaha 867D and I will reunite.

As for what happens next, we have no idea if my body will ever gain the kind of metabolic agility that I once enjoyed. I remain realistically optimistic, patient and open to infinite possibilities.

I guess that’s all that one can do in ‘the middle bit’.

My name is Imali; I’m 24 years old, a business owner/blogger and I live with a host of complex chronic health conditions - including ulcerative colitis, enteropathic arthritis, hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and currently, steroid-induced Cushing’s syndrome. I’ve been in and out of hospital since an early age, experiencing extreme fatigue, joint pain, and recurring infections. Like many with chronic illness, my journey has been anything but straightforward.

After developing particularly severe symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease in my early twenties, I was eventually diagnosed with ulcerative colitis. Despite trying multiple medications, things escalated and in 2024 my bowel perforated. I developed life-threatening sepsis and needed emergency stoma surgery to save my life.

Post-surgery, the hope was that things would settle down, but within three months it was found that I had developed enteropathic arthritis - a type of inflammatory arthritis linked to IBD - followed closely by uveitis in my eyes. To manage the extreme inflammation I had everywhere, I was placed on a high-dose of oral prednisolone steroids. They were meant to be a short-term fix while we figured out other treatment options. Unfortunately, my body has continued to react badly to the multiple alternatives, leaving me currently ‘stuck’ on steroids far longer than anyone expected.

That’s when the signs of steroid-induced Cushing’s syndrome started to show for me.

After a few months on steroids, I suddenly began to gain weight rapidly, my face and neck became round, my skin bruised easily, and I looked visibly swollen. I had a DEXA scan – which tests for your bone density – and it was found that mine was weakened down one side, a sure sign that the steroids were affecting me.

Although I had been warned of ‘moon-face’, nobody had told me much about Cushing’s syndrome, and so I didn’t know what to expect. Stuck on the same dose of steroids long-term, the weight just continued to gain, and I also now have the ‘hump’ in my neck, which I have realised is very common.

It wasn’t until reacting to my forth treatment option, that my GP mentioned the potential of Cushing’s syndrome to me and explained my symptoms, which of course, are textbook. This was really gratifying, because I found that I was struggling to understand how I was gaining so much weight and had such an appetite all the time. You could say it was a relief of sorts. It finally gave a name to the way I was feeling - but it also left me in limbo. I can’t stop taking steroids without risking my mobility or vision, but the longer I stay on them, the more damage they do. It’s a cruel balancing act.

What’s frightening is just how common this situation is. So many people with autoimmune and inflammatory conditions rely on steroids - often for longer than they’d like to - because other treatments aren’t accessible or don’t work. Yet hardly anyone is talking about the long-term risks of that. Steroid-induced Cushing’s syndrome is under-recognised, under-treated, and incredibly misunderstood.

Even celebrities like Selena Gomez, who have various chronic illnesses, have spoken openly about the effects of steroid treatment. Though she hasn’t confirmed a Cushing’s diagnosis, she’s faced extreme public scrutiny for the visible changes in her appearance - changes that many of us on steroids can relate to. It highlights just how little compassion or understanding there is when it comes to steroid side effects.

Living with Cushing’s on top of everything else is exhausting. I have found that my body is often physically changing quicker that I can mentally keep up with, and my relationship with food is a strange one because what I eat does not correlate to what I see in the mirror. I have also found that people are very quick to make comments about my weight, without any comprehension of the reasons behind it.

I’m currently working with my hospital teams to try and find a medication that I can tolerate so I can safely taper off the steroids. Until then, I’m stuck - and the reality is, so are many others.

Cushing’s syndrome is not “just weight gain” or “a round face” – it’s a serious condition that needs more attention and understanding. We need more awareness among patients and healthcare professionals alike, especially when steroid use is so common in treating autoimmune disease.

Imali is a disability advocate, content creator and co-founder of Inkfire Limited, the world's first disabled-led agency. Imali also shares lots of valuable and supportive content across her social media channels and website. You can see more of her content on her Instagram page (@mali.and.m.e) and on her website, www.maliandme.co.uk

To celebrate Cushing's awareness day, we've released a brand new Cushing's awareness video to help you understand Cushing's and spot its symptoms.

This video is developed by experts and explores what Cushing's is and what symptoms you may develop if you have Cushing's disease. You can find out more about Cushing's on our website.

This video was created by SIMBA CoMICS, in partnership with Professor John Wass and a lived experience review panel. You can read more about our lived experience reviewers below.

Lived Experience Reviewers

As well as being created and reviewed by endocrinology experts and clincians, this video was also reviewed by people with lived experience of Cushing's. In reviewing this video, our lived experience reviewers were able to provide valuable insights on tailoring the messaging of this video to meet the needs of people living with Cushing's disease.

We want to say a huge thank you to our two lived experience reviewers, Pauline Swindells and Caz Brown, for their involvement in this video.

Pauline Swindells

Pauline was diagnosed with Cushing's disease 10 years ago, at age 62. Her tumour was found by chance, however it didn’t start secreting excess ACTH until 18 months later, when she was then diagnosed and had surgery.

Although a retired nurse, she didn’t know a lot about Cushing’s disease but The Pituitary Foundation website was a great resource. Looking on Facebook, the only groups she found were US-based. Nine years ago, she decided to start a UK-based group which now has over 2800 members, although not all will have Cushing’s. Pauline likes to research and read new papers about Cushing’s so information can be shared with the group, giving members up-to-date information and enabling them to advocate for themselves when needed.

"I’d like to say I’m back to my pre-Cushing’s self but I’m not, I’m still steroid dependent & have other issues, not all related to Cushing’s, however it does mean I can spend lots of time on the group supporting & helping members alongside the other admins."

Caz Brown

Caz was diagnosed with Cushing’s disease in 2018 and has been in remission since her surgery in 2019, after having symptoms for 4 years. The Pituitary Foundation and the Cushing’s UK support group helped throughout the whole journey with valuable information, support and insights into the process, including advice on returning to work.

Since Christmas 2022 she has been volunteering for The Pituitary Foundation, initially as an admin in the Cushing’s UK support group, responding to enquiries submitted about Cushing’s on The Pituitary Foundation website and helping to run zoom calls. More recently, she has become a Pituitary Ambassador, helping to spread awareness of the charity to patients and medical organisations. She has also helped at some of the in-person get togethers, including talking about her journey and being a welcoming face for the attendees.

For more support and information about Cushing's, you can join the Cushing's UK Facebook group.

Professor Niamh Martin is a professor of Endocrinology at Imperial College London. She is also an honorary consultant in Diabetes and Endocrinology and a consultant physician at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICHNT), London

Alongside this article, Prof Martin also delivered a talk about Cushing's and its treatment. You can watch this talk below.

What is Cushing’s Awareness Day?

The 8th of April is Cushing’s Awareness Day. To mark this day in 2025, I have been invited to talk to The Pituitary Foundation online about Cushing’s disease and to write this article to highlight recent research in Cushing’s disease.

In 1912, Harvey Cushing described a series of 12 patients, all young adults, with features which we now recognise to be consistent with Cushing’s disease and proposed that these resulted from a pituitary tumour causing this condition. The date of Cushing’s Awareness Day has been chosen as it was Harvey Cushing’s birthday. Harvey Cushing was a remarkable man; in addition to his description of the eponymous Cushing’s disease, he was also responsible for introducing blood pressure as an essential observation in clinical practice and won a Pulitzer prize for his biography of Sir William Osler, a widely celebrated physician and medical educator.

What is Cushing’s?

In the first instance, it would be helpful to review terminology. Sometimes ‘Cushing’s’ is referred to as Cushing’s syndrome and sometimes as Cushing’s disease. Cushing’s syndrome is a condition where the body is making too much of the hormone cortisol, causing a number of typical clinical features.

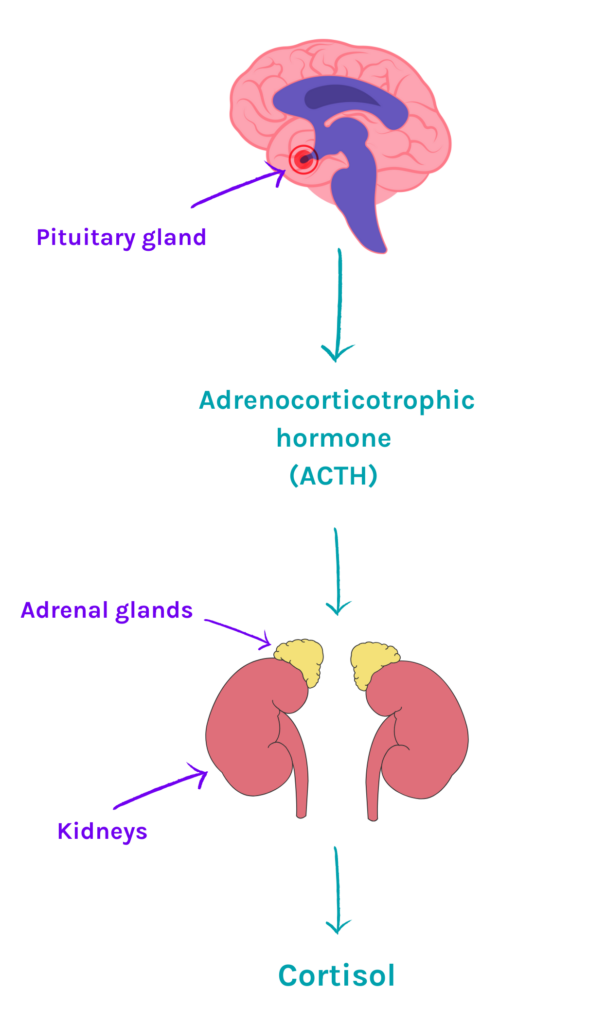

There are two adrenal glands, one sitting on top of each kidney. The adrenal gland has an outer layer called the adrenal cortex and an inner layer, the adrenal medulla. The adrenal cortex makes several important hormones, including the hormone cortisol. The inner medulla makes our ‘fight and flight’ hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline.

Cortisol in health and disease

Cortisol has a diurnal (daily) or circadian rhythm, with levels increasing in the early hours of the morning and becoming highest as we are getting out of bed to start the day. As the day progresses, cortisol falls and by bedtime, cortisol levels are low. As you can imagine, shift-workers have an altered diurnal rhythm in cortisol as their daytime and night-time may be reversed.

The adrenal glands need to be told to make cortisol by a hormone which comes from the pituitary gland. This hormone is called adrenocorticotrophic hormone, which is abbreviated to ACTH. As mentioned, the term Cushing’s syndrome describes any condition where cortisol levels are high in the body.

This includes situations where patients have been prescribed high doses of steroid treatment for another medical condition, for example asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. If the cause of Cushing’s syndrome is a pituitary tumour making increased amounts of ACTH, which in turn stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce excessive cortisol, this is called Cushing’s disease.

Clinical features of Cushing’s

Some of you reading this article will have had a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease. There are many clinical features and so as a result, patients may come to medical attention in different ways. Patients may present with weight gain, high blood pressure, newly diagnosed diabetes, or may have a fracture, since too much cortisol can cause osteoporosis.

Alternatively, patients may notice a change in their appearance, with a rounder face, which may be red (plethoric) and women may experience disturbances in their periods and increased hair growth on their face. Too much cortisol has negative effects on skin and muscle, so patients with Cushing’s may report easy bruising, thin skin, painful red stretch marks, and weak muscles, making activities like climbing stairs often difficult.

Treatment of Cushing’s

Usually, the first approach for treating Cushing’s disease is removal of the ACTH-producing pituitary tumour. This operation is performed by a neurosurgeon and usually, the approach is via the nose, as the pituitary gland sits at the base of the skull behind the eyes. Sometimes, patients with Cushing’s disease require medication for a period of time before surgery to reduce cortisol levels in the blood. This depends on several factors, including the wait for surgery and also how symptomatic the patient is from high cortisol levels.

Similarly, there may be patients whose Cushing’s disease is not cured by surgery or may be unable to have surgery due to additional medical conditions. Radiotherapy (deep X-ray treatment) is an alternative to surgery, but this is slow to take effect. Therefore, in these situations, medication to lower cortisol may be needed in the medium-term after radiotherapy and for the longer-term, if surgery is not an option.

New areas of Cushing’s research

Osilodrostat

Osilodrostat is a new medication which has been developed to lower cortisol in patients with Cushing’s. There have been joint studies between hospitals in the US, Europe and the UK showing that osilodrostat is effective in reducing cortisol and is well tolerated. In these studies, the UK has been represented by Professor John Newell-Price in Sheffield, who has extensive clinical and research experience in Cushing’s.

Dr Florian Wernig, a consultant endocrinologist working at Imperial College London, is collaborating with Professor Mark Gurnell and colleagues in Cambridge to carry out the OPTIMAL (Osilodrostat therapy and 11C-methionine PET to IMprove corticotroph pituitary Adenoma detection and Localisation in patients with Cushing's disease) study. The initial steps for diagnosing Cushing’s disease includes hormone measurements in blood, urine and saliva, (with specific tests varying between centres). Once Cushing’s disease is suspected, an MRI (a special scan of the pituitary gland) is organised to look for the ACTH-producing pituitary tumour. Sometimes, these tumours can be difficult to see on MRI scans as they can be very small or not easily distinguishable from the pituitary gland itself.

The OPTIMAL study uses a special nuclear medicine technique, available from Professor Gurnell’s research team at Cambridge, called 11C - methionine PET CT, to visualise the pituitary gland in a different way to MRI. Dr Wernig suggests that using osilodrostat to safely reduce cortisol in patients with Cushing’s disease, who don't have a visible pituitary tumour on MRI, may stimulate the ACTH-producing pituitary tumour to be more active. This may make it show up more clearly on 11C - methionine PET CT scans. Clearer identification of the ACTH-producing pituitary tumour will help the neurosurgeon focus on where the pituitary tumour is located during surgery.

The OPTIMAL study aims to investigate whether this is a potential pathway to assess patients with Cushing’s disease who do not have a clearly visible tumour on their MRI scan. The OPTIMAL study is currently underway, so we look forward to hearing the outcome of this study in the next year or so.

Post-surgery procedures

After successful surgical removal of the ACTH-producing pituitary tumour in Cushing’s disease, patients are usually placed on steroid replacement in the form of hydrocortisone or prednisolone for a period of time, with the aim to slowly reduce this. The reason for this is that in Cushing’s disease, the normal ACTH-producing pituitary cells are ‘sleepy’ as a result of the busy ACTH pituitary tumour cells. This means that early after pituitary surgery, the ACTH-producing pituitary cells are not working and need some time to ‘wake up’ and function normally.

Professor Karim Meeran at Imperial College London is investigating the best approach for weaning patients off hydrocortisone or prednisolone after pituitary surgery. His clinical research team are studying different approaches to this using patient-friendly protocols that can be easily followed by patients and their clinical teams.

Relacorilant

Relacorilant is a newly developed drug which has been submitted for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in the US as a potential treatment for Cushing’s syndrome. This drug works by blocking the receptor that cortisol binds to, called the glucocorticoid receptor. This stops cortisol from producing negative effects in the body. Clinical trials are underway to investigate how clinical teams may be able to use this drug.

ST002 / Fluasterone

A very new drug called ST-002 (also known as fluasterone) is being studied in some very early clinical trials to also see whether this may have a role in Cushing’s management. This works by blocking cortisol production from the adrenal glands. We will need to watch this space about both this drug, and relacorilant, in the months and years to come.

The diagnosis of Cushing’s may sometimes be slow, as typically symptoms progress quite gradually and there is an overlap with medical conditions seen quite commonly in the general population. However, it is important to make the diagnosis accurately, to ensure patients receive the correct treatment. I hope this article has given you an overview of Cushing’s, including some interesting research developments.