Dr Trevor A Howlett, MD FRCP

Consultant Endocrinologist, Leicester Royal Infirmary

Doctors who are not specialists in endocrinology often have difficulty interpreting thyroid blood tests in patients with pituitary disease which can lead to failure to diagnose a mild deficiency and inappropriate changes in levothyroxine dosage in patients taking replacement.

This article attempts to explain the problems with interpretation of thyroid blood tests in pituitary disease to help you to become an ‘expert’ in your own pituitary-thyroid function.

In normal health, the thyroid gland makes thyroid hormones which broadly keep all the cells and organs of the body ‘ticking over’ at the correct rate. With too little thyroid hormone in the body, everything slows down and symptoms may include tiredness, slowness in thinking, weight gain, constipation and dry skin. Conversely with too much thyroid hormone everything speeds up and people may notice a fast heartbeat and increased risk of heart rhythm problems, weight loss, sweating and shakiness.

Thyroid hormones in the blood are thyroxine (measured as “free T4” on the blood sample) and triiodothyronine (“free T3”) – these are produced by the thyroid and the amount produced is controlled by levels of the pituitary Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (“TSH”). In normal health the brain and the pituitary are able to sense the amount of free T4 and free T3 circulating in the blood and adjust the amount of TSH produced by the pituitary so that levels of free T4 remain in the normal range (in much the same way as a central heating thermostat turns on the heat when the temperature is too low and turns it off when the temperature is too high). This sort of control mechanism is known as “negative feedback”.

Thyroid blood tests (“thyroid function tests” or “TFTs”) commonly measured by the laboratory include free T4 and TSH. The range of free T4 seen in normal healthy people is very wide (broadly from 10 to 25 pmol/L) but each individual normally runs at a fairly constant level somewhere within this range. This in turn means that a level of free T4 near the bottom of normal might be too low for some people (who usually live higher in the normal range) and equally a level near the top of normal might be too high for someone who normally lives near the bottom of normal.

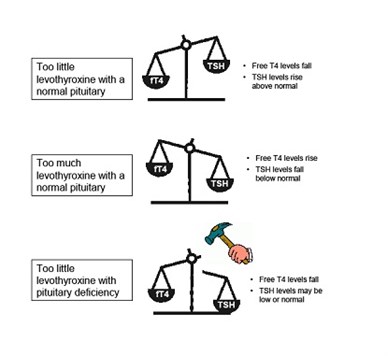

Luckily, for most people with a normal pituitary, levels of TSH in the blood allow us to sort this out because if free T4 levels are too low for an individual then their TSH production is turned on and levels rise above normal – and conversely if free T4 is too high then TSH is suppressed (see diagram). Doctors can therefore rely on TSH to accurately judge when someone with a normal pituitary is making too much or too little thyroid hormone. They can also use TSH levels to assess whether someone with a thyroid deficiency is having too much or too little replacement with levothyroxine (which is T4 in a tablet) and we normally aim to keep TSH in the normal range to optimise replacement.

Because of the usefulness of TSH, many labs will now only measure TSH when a non-specialist orders thyroid function tests or TFTs (this saves money and is absolutely fine for the vast majority of tests which the lab performs in people who have nothing wrong with their pituitary).

Unfortunately this all goes wrong in pituitary deficiency! If the pituitary fails to make enough TSH then free T4 levels in the blood will fall – but since the problem is at pituitary level then TSH levels in the blood do not rise appropriately. In severe cases free T4 will fall below the normal range, while TSH levels can be normal or low (see diagram). If the patient then receives levothyroxine replacement for their thyroid the free T4 levels will rise, and TSH levels often fall to below normal.

This means that TSH levels alone are useless for deciding whether someone with pituitary disease has developed a pituitary-thyroid deficiency or whether they are on the correct amount of levothyroxine replacement (or too much or too little).

Endocrinologists are aware of this problem, and will usually always request a free T4 measurement from the laboratory in patients with pituitary disease. However, your GP may not be so lucky if they request “TFTs” and will often only get back a TSH result. In my experience, this often leads to inappropriate reductions in levothyroxine dosage by the primary care team – when a low TSH level is interpreted as a sign of too much levothyroxine (which is true in people with thyroid problems) rather than as simply a sign of the pituitary deficiency which is being treated.

However, even endocrinologists have problems knowing exactly what a lowish free T4 level means because of the wide range of free T4 in normal people. A common dilemma is whether a level in the lower part of the normal range represents a deficiency (for someone who would run in the higher part of normal if nothing was wrong with their pituitary) or is simply the normal level at which that person has always been.

Equally, when a decision has been made to start levothyroxine replacement it is difficult to know exactly what free T4 level to aim for. Traditional recommendations suggest aiming for the “upper half of the normal range” – but if we did this in everyone then by definition half the people treated might be running higher than their previous normal level. There are potential risks from giving too much or too little levothyroxine so ideally we would like to get things as normal as possible.

In order to find out more about this, we reviewed the results of thyroid blood tests in all patients with pituitary tumours in our department and we have recently published the results in the UK medical journal Clinical Endocrinology. We looked at results of tests in over 500 pituitary patients, almost 150 of whom were taking levothyroxine – and we compared the levels we found with over 20,000 sets of thyroid blood tests in patients with problems with the thyroid gland itself who had a normal pituitary.

We were pleased to find that we had indeed measured free T4 levels in almost everyone, and that very few people had levels outside the normal range. However, we were less pleased to discover that many more patients with pituitary disease had levels of free T4 in the lower part of normal when compared to patients we were treating with thyroid disease. Overall we suggested that this means that we are probably failing to diagnose and treat mild levels of pituitary-thyroid TSH deficiency in some of our patients, and that we are not giving many of our pituitary patients enough levothyroxine to keep free T4 levels up to the range which we know represents optimal replacement in people with a normal pituitary.

We suspect that the same thing will be happening in many other places. We were able to do this study because we have collected details on diagnosis and treatment of all our patients in a clinical database for over 20 years and therefore have detailed information on large numbers of patients with pituitary disease and thyroid disease, with all the thyroid blood tests checked in a single hospital laboratory and available for comparison. Most other places would not be able to pull together all this information to compare results in their centre – but if they could we think it is likely they would find the same thing.

We therefore made some preliminary suggestions for more appropriate cut-offs and treatment targets for free T4 levels in patients with pituitary disease. Precise numbers will probably vary from laboratory to laboratory around the country – but broadly our recommendations were as follows:

Please note that recommendations only apply for patients with a large pituitary mass (macro adenoma) or after pituitary surgery or pituitary radiotherapy:

- Have a high index of suspicion for mild deficiency of TSH in patients with free T4 levels in the lower part of the normal range.

- Have a low threshold for levothyroxine treatment in patients near the bottom of normal (in our laboratory a free T4 ≤ 12pmol/L) whether or not there are symptoms, particularly if other pituitary deficiencies are present.

- Consider levothyroxine treatment for patients with higher levels who have any symptoms of possible deficiency (in our laboratory a free T4 ≤ 14pmol/L).

- Aim for free T4 levels in the middle of the normal range in pituitary patients on levothyroxine replacement (in our laboratory target free T4 16pmol/L and range 14-19 pmol/L)

We are now introducing these guidelines in our own department, and plan to monitor the responses of patients in whom the new guidelines result in a change of treatment.

So what does the patient with pituitary disease need to do if they wish to be sure that their thyroid levels are appropriate? I suggest:

- If you have a macro adenoma and/or have had pituitary surgery or radiotherapy then you are at risk of TSH deficiency, especially if you also need other pituitary replacement treatment.

- If you only have a micro adenoma and have never had surgery then the risk of deficiency is very low.

- If you are feeling perfectly well and your GP or endocrinologist says that your thyroid levels are fine then it is reasonable to assume that nothing needs to be done.

- If you are not feeling well with symptoms which could be caused by thyroid deficiency (e.g. tiredness, slowness, and weight gain) then it is always worth asking whether your free T4 level is running in the lower part of normal. This applies whether you are on replacement or not, and our treatment recommendations are given above.

- If you are taking levothyroxine for pituitary TSH deficiency, beware advice to reduce dosage after a blood test in primary care. Ask “is this because my TSH is low or because my free T4 level is too high?” If the answer is because of a low TSH (or if they can’t or won’t tell you) then contact your endocrinologist for advice.

Thyroid hormones are easy to measure and easy to replace, but we may all need to be more generous in what we consider to be really “normal” if we want to achieve optimal thyroid levels in all pituitary patients.